Large-bodied consumers are increasingly lost from ecosystems due to hunting and fishing pressure from humans. As these consumers are critical drivers of community structure and ecosystem function, its crucial to evaluate the cascading effects of their disappearance.

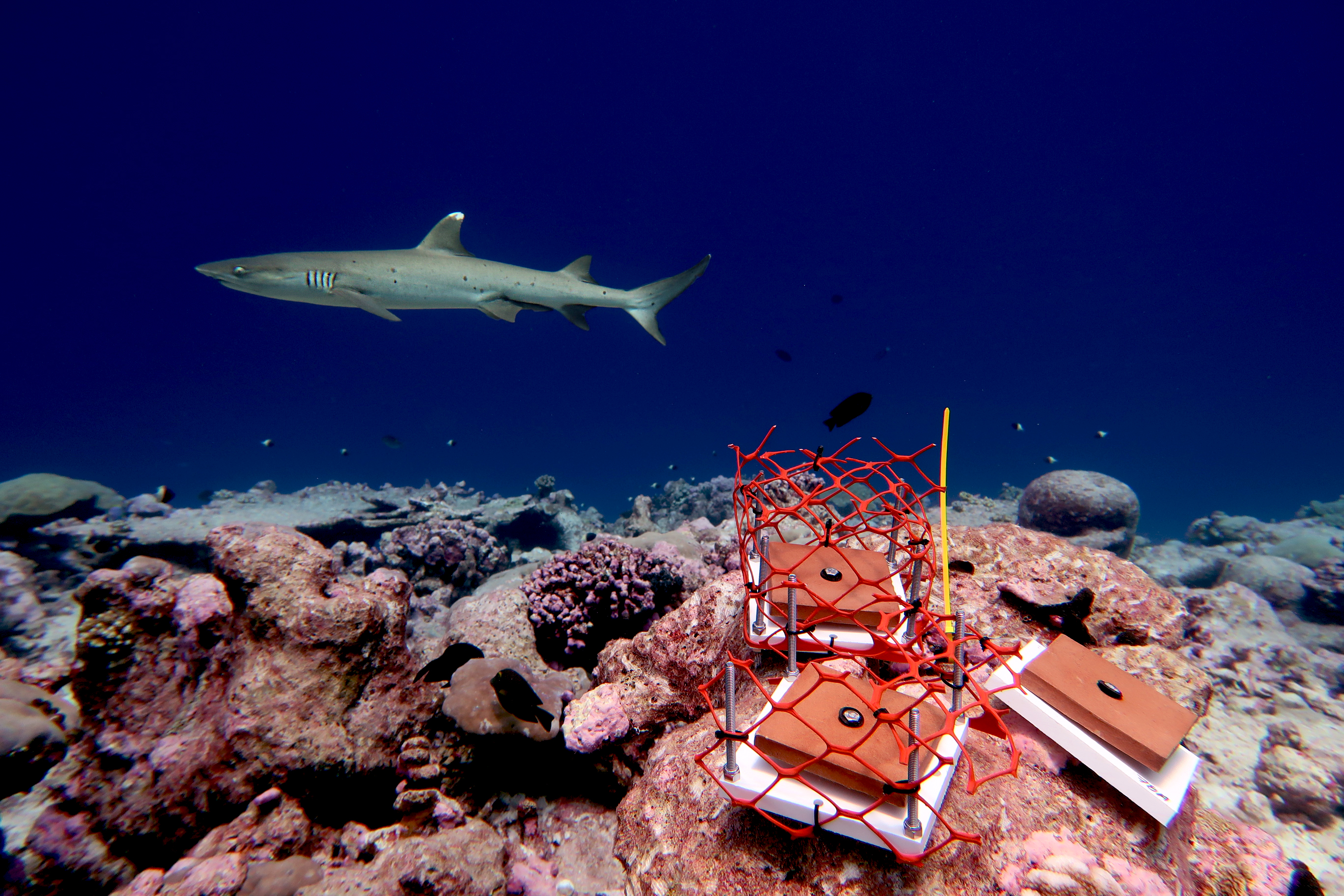

Fishes play integral roles in structuring coral reefs by limiting algae that compete with corals; however, reefs are rapidly losing large fishes due to fishing pressure. Using an experiment at Palmyra Atoll, we found that the loss of fishes on coral reefs can increase the variability and decrease the predictability of coral reef benthic communities (McDevitt-Irwin et al. 2023, Oecologia). Reefs are also facing dramatic declines in their shark populations, but there is very little research on how the loss of sharks may cascade through the food web to reef recovery. We found that the remote and protected Chagos Archipelago exhibited compensatory dynamics within the fish and benthic community that maintained key processes across a gradient of shark abundance and when fish are excluded (McDevitt-Irwin et al. 2024, Biological Conservation).

Most community ecology research captures a static snapshot of a dynamic process, largely ignoring how species interactions vary across time. In Palmyra Atoll, we demonstrated that fish promote initial coral recruitment after a disturbance, but their effects diminish after three years (McDevitt-Irwin et al. 2023, Sci Rep). In the rocky intertidal in California, we found that the timing of when herbivores arrived after a disturbance influences short-term but not long-term algae community composition, demonstrating this strong and deterministic top-down control in this ecosystem (McDevitt-Irwin et al. In Prep).

I am currently co-leading a NSF LTER Working Group exploring how the loss of consumers across marine, terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems affects community variability across space (i.e., dissimilarity in community composition).

Experiment in the Chagos Archipelago, Photo Credit: Kristina Tietjen